Magnetic Particles

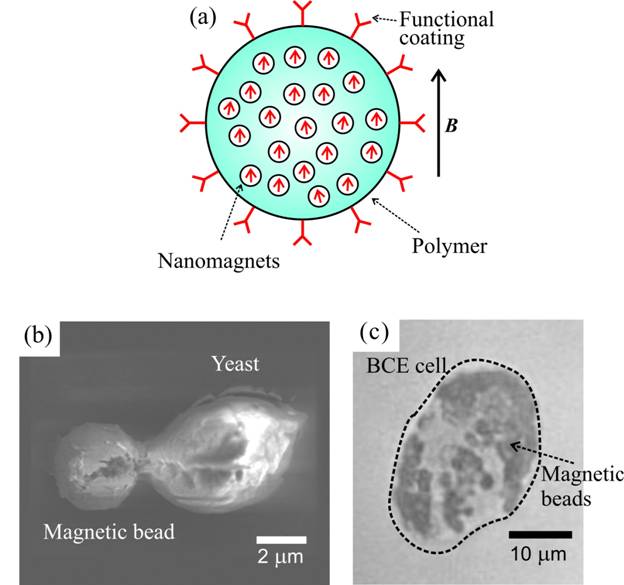

A number of companies offer magnetic microbeads suitable for many biomedical assays. The magnetic component of these particles is basically iron oxide, usually in the form of maghemite (gamma-Fe2O3). Typically, nanometer-sized particles of iron oxide are dispersed in, layered onto, or coated with a polymer or silica matrix to form beads about 1 micrometer in diameter. Nanometer-sized particles of iron oxide are only magnetic in the presence of a magnetic field; the particles immediately demagnetize when the field is removed, so the beads do not attract each other and aggregate.Carboxy-ferromagnetic beads from a company calledSpherotech with amino-fluorescein attached.

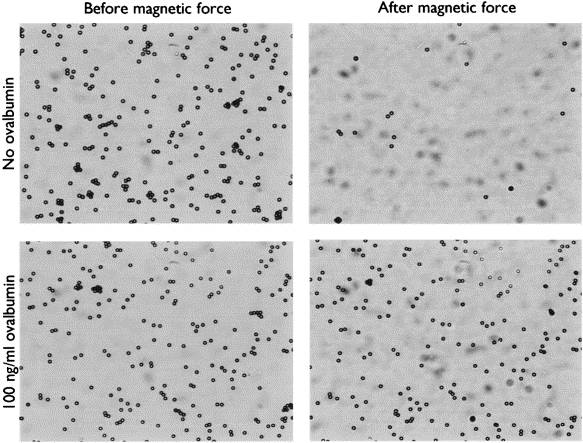

Iron oxide is the favored magnetic component because of its stability. However, since it is a ferrimagnetic material, it is not highly magnetic. What is more, commercial magnetic beads generally contain only 10 to 60 percent iron oxide. Therefore, it is very difficult to exert more than 10 pico newton of force per bead. Forming a force that encompasses the expected antibody and antigen unbinding force of 100 pN would require fabricating highly-magnetic beads. To date, however, such beads tend to agglomerate due to magnetic domain fringe fields or inadvertent magnetization. Another approach would be to use micrometer-scale magnets, as in the approach of Hoh et al. (1994). Small magnets can generate very large field gradients; however, since they only affect a small area they must be scanned over the sample. The following is Fluorescent beads inside HeLa cells, fluorescent microscope image.

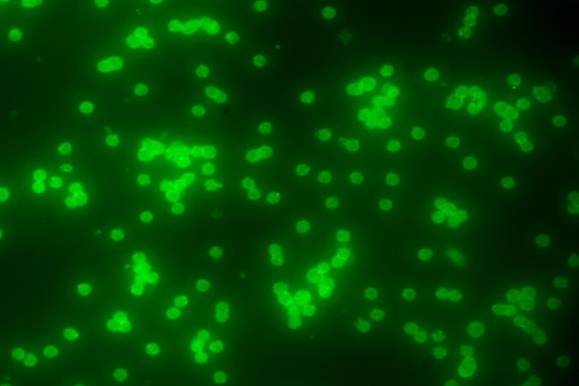

The following is Fluorescent beads inside HeLa cells, microscope image.

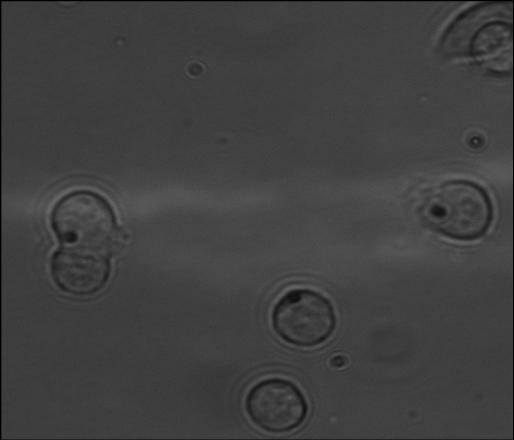

The following is magnetic beads inside yeast cells and BCE cells, microscope image.