ACL damage/current treatments

Website made by Shia-Yen Teh ( 2006)

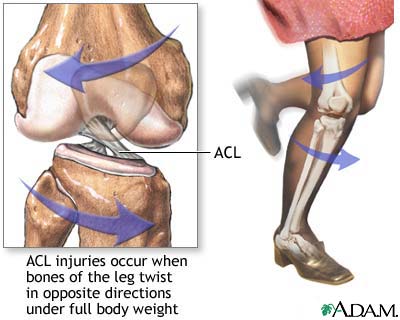

ACL damage usually occurs during an athletic activity. A common cause is when the leg is rotated inward as the rest of the body is turning outward. These motions occur as an athlete is quickly changing direction, which is the cutting motion observed in basketball, football, and racquet sports.

Damage to the ACL most often results in complete tears, which is followed by redness and swelling of the knee. An ACL injury can be painful, and will prevent the person from continuing to participate in high agility activities, and may hinder normal knee function. Computer simulations have been done to show the difference between a person with an intact ACL and a torn ACL. (Videos courtesy of Rob Kroeger) A torn ACL leads to an unstable knee and poor gait. Due to poor healing properties and minimal vascularization, the ACL does not heal on its own. Individuals who do not normally take part in high impact sports may choose to live with the disability, but most athletes opt for ACL reconstruction surgery.

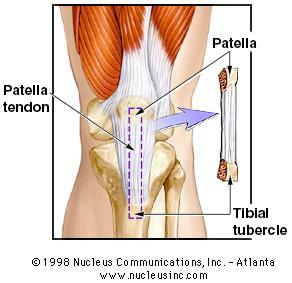

The current gold standard for replacing the ACL is by grafting with a section of the patella or hamstring tendon harvested from the patient. For most people, reconstruction using autografts are sufficient for a period of time, but it does not perform well in the long-term. The graft can be taken from either the healthy or the impaired knee, and is held in place with metal or bioabsorbable screws. Some problems with this method are that it forms an extra wound site and it does not provide the same mechanical properties of the original ligament, since tendons have different amounts of protein and cellular components than ligament, thus have different mechanical properties. There is also the issue as to how the function of the recovering patellar or hamstring tendon will be altered. Weakening of either of these tendons can contribute to instability of the knee. The long-term performance of ACL grafts is also questionable. A high percentatge of grafts have exhibited creep, fatigue and mechanical failure within several years of implantation.

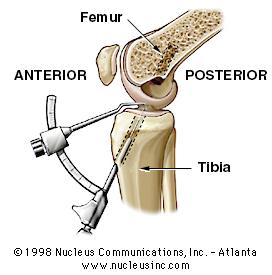

During surgery, the surgeon uses an arthroscope to image the damaged area and determine the exact location for grafting. The graft can be from either the patella tendon or hamstring tendon, but the patellar tendon is used most often. The central third of the patellar tendon is harvested, with bone blocks intact at each end of the graft.

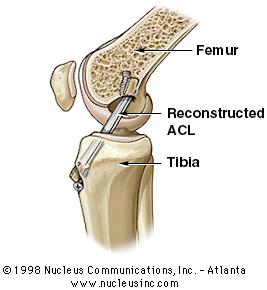

Following harvesting of the graft, holes are drilled into both the femur and tibia to serve as guides for the implanted graft. The holes are drilled in the attachment sites of the original ACL to ensure proper placement of the new graft.

The graft is pulled through the drill holes and held in place with metal or bioabsorbable screws.

Drilling into the bone also serves to promote healing by introducing blood flow into the wound site and initiating the growth of new blood vessels into the graft area. After surgery, the patient undergoes physical therapy for 6 months to recover full range of motion and to strengthen the muscles around the knee